Approaching arts – and human experience in general – from the perspective of multimediality can be fruitful in opening different ways of understanding these experiences. We perceive the world first through our bodily senses and then construct various understandings and experiences of this sensory data through complex cognitive processes. While much of these experiences are non-conceptual I will here discuss mostly the ways in which music is conceptualised by using terminology from other artistic media. I. e we understand – or communicate our understandings of – music using words originally, or more often, used to describe other artistic media or realms of human experience.

Multimediality in music begins with one of the oldest ways of music-making; singing. Although, as discussed before, singing may actually have preceded language and been a sort of “protolanguage”, singing as we usually think of it includes text, lyrics.

Intermediality and intertextuality

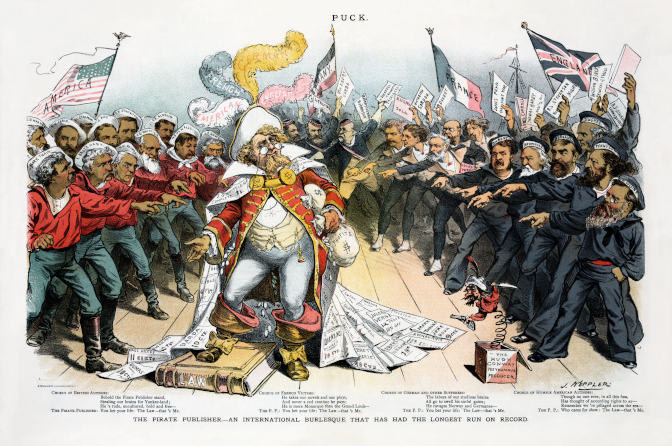

Multimediality cannot really be discussed without also addressing some neighbouring terms. Intertextuality became hip in the academic discussions of arts since at least in 1980s. It’s a helpful tool in analysing and understanding the ways in which meanings are created in multifaceted ways by various techniques such as quotation or some sort of reference. As discussed before, these techniques have been central to black American music-making since the times of slavery to the contemporary hip-hop.

Intertextuality tends to fall short when applied to performing arts. While there are certain benefits in reducing everything to “texts”, two dimensional layers of meaning, this comes with a cost when studying music as a performative phenomenon, e.g. through Christopher Small’s “musicking”. Multimedality is a more helpful concept in helping us study and understand how different artistic media are used, and can be used, to reflect and create rich human experiences by drawing from the tools and strengths of the different media in our disposal.

Multimediality in music

Multimediality in music is an old idea as music has always been a part of some “extramusical” performance or context such as a ritual. In fact “pure” music is one of those 19th century Romantic ideas still to some extent holding our experience of music captive. But more about that another time.

The gesamtkunstwerk of Richard Wagner‘s opera remain perhaps the most iconic examples of effort to bring all the art forms together. Whereas Wagner’s operatic works might stand as the ultimate artistic expression of modernity, the 21st century post-modern artists produce more fragmented works.

Whereas black American music has got from the cotton fields to White House (see below), western Classical music is now performed by native orchestras and singers all over the world – here also conducted by a woman, something which in Wagner’s time was quite unthinkable. Multimediality here includes also video projections and TV production.

Earlier I discussed how Jacob Collier presents his multifaceted talent in his YouTube videos and how Janelle Monáe implies multiple – or perhaps fragmented – identities in her performances of the song Tightrope with means of music production, the “music itself” (e.g. melody, harmony, groove), lyrics, video, live performance, etc. The Dutch group Tin Men and the Telephone is also a very interesting example of musical art that draws from multiple media in a very interactive way on and off stage.

Janelle Monáe’s performance in the White House by Barak Obama’s invitation has various multimedial layers. As discussed earlier, her performance style is rich in references to other black American artists, perhaps most notably in the James Brown steps in her dance moves. In this performance the “Funkiest horn section of Metropolis” becomes that of White House, opening up a myriad of interpretations.

Here’s Jacob Collier embracing the social medium of music making in a contemporary digital manner enabling music-making together across temporal and spacial boundaries.

Tin Men and the Telephone do various things with different media from “musicalising” recorded speech and other sounds to typing with the piano keyboard and collaboration with their audience through a special app.

Music in literature – Toni Morrison’s Jazz

One interesting form of multimediality is that of music in literature; the use of description of music in literature and use of musical techniques in writing. Describing music in words requires quite an effort from the writer and reader alike to convey and share an artistic experience across the media. To describe art of one medium with the means of another requires sharing cultural understanding on a deep level and the ability to imagine, in this case, music described with words.

One interesting form of multimediality is that of music in literature; the use of description of music in literature and use of musical techniques in writing. Describing music in words requires quite an effort from the writer and reader alike to convey and share an artistic experience Jazz by Toni Morrison, 1st edition cover across the media. To describe art of one medium with the means of another requires sharing cultural understanding on a deep level and the ability to imagine, in this case, music described with words.

When I first tried to read Toni Morrison’s Jazz, in the age of around 15 or so, I expected it to be “about jazz”. I didn’t understand much about it and quickly gave up.

Recently I picked up the book again and was better able to appreciate the ways in which Morrison took jazz as a metaphor and method and used its compositional and performative techniques to tell the story of her book.

Like a jazz performance the book has a main theme, a story it wants to tell. However, the main characters are also given “solo spots” to elaborate on their personal stories giving depth to the main story and enabling the reader to approach – perhaps even experience – the story from the individual perspectives of the characters; much like in jazz performance the “tune” is approached differently by each of the soloists.

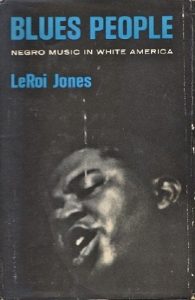

Jazz in Morrison’s book is also a metaphor for the black American struggle and experience. As briefly discussed before, jazz has come a long way from an unappreciated folk music symbolising the worst of human kind – even among some black Americans – to be heralded as the “American Classical music”. Whereas Amiri Baraka in his Blues People elaborated on the idea of “music as the history of black Americans”, Morrison gives the bones of this history the flesh of her characters.

At the time I’m typing this the first black American president has just stepped aside to make space for yet another white male, one whose rhetoric and first deeds clearly show how the struggle for human rights is far from over. Morrison’s story takes place in a period prior to the Civil Rights era when many – as some of the characters in the book – still had vivid personal memories of the Jim Crow treatment of blacks.

Music and visual arts

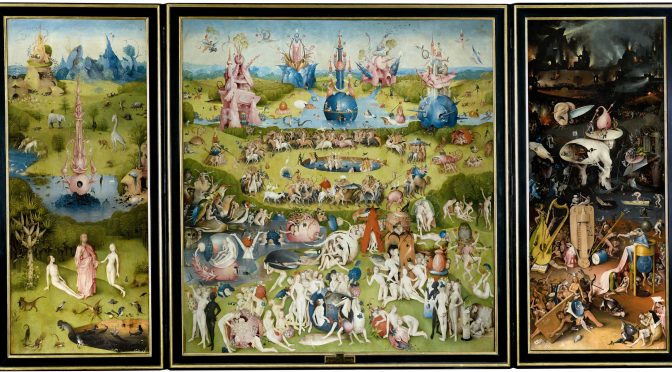

The painting on top of this article is the Garden of Earthly Pleasures by Hieronymus Bosch from 1500. As sound is difficult to picture music in visual arts is mainly pictured through instruments and musical acts such as dancing and singing. Bosch’s painting is a classic one portraying music as a sinful – or at least not respectable – activity through placing some instruments of the time together with people busy with Earthly orgies.

The pianist Bill Evans wrote liner notes for the 1959 Miles Davis quintet album Kind of Blue, I’ve also discussed earlier. In his text Evans makes an analogy between the Japanese calligraphy shodō and jazz improvisation. He stresses the temporal nature of both media; just as the stroke of a brush leaves its mark on the paper and cannot be undone or altered, a musical sound cannot be taken back. Further challenge in jazz improvisation is the group setting in which it most often happens; there are in fact many “brushes” making strokes simultaneously to the “canvas” of temporal framework set, in this case, by Miles Davis.