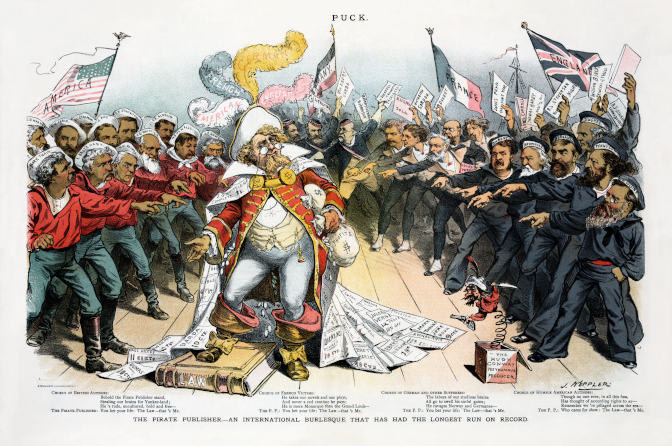

I’ve always found it peculiar that the copyright laws applied to music are the same ones – with slight adaptations – applied to tangible creations of the human spirit, most importantly literary works. Of course this shouldn’t be surprising as these laws date back to the invention of press and the control of this powerful means of disseminating written word.

Motivations for creating legislation to protect intellectual property have mostly been economical. The Licensing of the Press Act of 1662 in England granted the king the control over printed works. The Statute of Anne of 1709 is considered the first copyright law granting the authors some specific rights to their works.

As the copyright laws have later been extended to cover works in other than strictly literary media, such as music, film and visual arts, some interesting ontological questions have come up, a few of which I’d like to take up here.

Copyright in the age of mechanical reproduction

Around 1900 technological reproduction had reached a standard at which it had not merely begun to take the totality of traditional artworks as its province, imposing the most profound changes on the impact of such works; it had even gained a place for itself among artistic modes of procedure,

Walter Benjamin, The work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction (1936)

|

Early camera

|

Benjamin wrote the above at a moment when, the still relatively novel art form of, cinematography was approaching its golden era having just moved from silent films to the “talkies” (see here for more about silent film). In music a similar moment could be said to have been reached half a century later when the emerging hip hop musical practices “changed the game” and started a whole new development, or at least gave it a boost.

As discussed above the whole idea of, and need for, copyright arose from the necessity to control the implications of the “mechanical reproduction” of art Benjamin writes about. But as often happens with objects, technologies, and just about everything people invent, others think of uses for them no one could imagine at the emergence of these novelties.

One of the rights copyright legislation grants to the author is a control of, and compensation for, derivative works based on his/her original work. The emergence of hip hop and rap in the late 70s and early 80s challenged this legal – as well as artistic – relation between the “original” and “derivative” work.

The way this new music challenged, not only the legal norms, but the norms of Western music in general transforming in the musical context the whole notion of “traditional artwork” Benjamin refers to above, deserves a larger discussion than possible right now. In his thesis about hip hop and Afrofuturism Chuck Galli explains how hip hop got started in South Bronx partly as a result of urban planning isolating a group of mainly Blacks and Latinos without means of relocating themselves and leaving them with few socio-economical opportunities. Making ends meet also artistically in lack of musical instruments record players – or turntables – were turned into instruments using records as musical material. The DJs began looping some of the grooviest parts of the records they got their hands on to give their audiences something to dance on. While the DJ was sampling the grooves off of his records an MC would pick up the mic and improvise – later dubbed as “freestyle” – rhythmical verbalisations on the grooves to further engage the audience with the moment. Later these creations were also compiled into remixes recorded onto C-casettes and distributed.

Stevie Wonder’s still relevant Living For The City from 1973 describes the reality many Blacks faced during the period.

As discussed before, African Americans have a history of reinventing their musical culture as it gets appropriated by the mainstream culture. Hip hop continues this tradition but turns on another gear. The DJ’s adaptation of the turntable from a tool of reproduction to an instrument of creative musical production, not only turns around the role of this piece of technology, but also challenges our very definition of music as the audible result of certain creative practices and processes.

In the late 1980s James Brown released his musical response to the “copycats” who had been sampling his music for a long time. For more about this multifaceted statement see here. Here‘s an interesting discussion about sampling with some legal experts and Mr. SHOCKLEE from Public Enemy.

It’s therefore not surprising that the copyright legislation, dealing with tangible representations of music e.g. in written/printed and recorded forms, has had difficulties dealing with this form of artistic (re)production challenging the notions of originality and authorship of a musical work. This difficulty in many ways culminated in the 1991 case Grand Upright Music, Ltd. v. Warner Brothers Records, Inc. in which the judge ruled in favour of the plaintiff and changed the way hip hop has been made since by stating that every sample of another artist’s recorded work has to be licensed.

Whiter shades of the Grey Album

The DJ takes a sample to create out of it both a unique sound and a unique emotion. Having one’s music sampled, far from being an insult, can easily be interpreted as a compliment since, the logic goes, an artist’s work was so good that there is no point in trying to imitate it – just use the actual piece. One’s work is thus taken whole and placed into a new work and, most importantly, manipulated through various DJ techniques (altering the tempo or pitch, scratching the sample, etc.) and through the juxtaposition of the sampled bit with other samples… hip-hop takes data and synthesizes it into a new “whole” which provokes emotion not only from the primary experience of hearing the sounds, but from understanding where the sounds come from and what impacts such an understanding may have.

Chuck Galli, Hip-Hop Futurism: Remixing Afrofuturism andthe Hermeneutics of Identity

The Grand Upright ruling was directly against the very essence of hip hop as a musical practise, as Galli above describes it. From the early days of the art form hip hop artists embraced sampling in all forms and also encouraged their fellow artists to use their samples by releasing them separately. This is also what Jay-Z did by releasing an a cappella version of his Black Album, which indeed was subsequently remixed by many DJs.

In late 2003 DJ Danger Mouse, aka Brian Burton, set upon himself a challenge of mixing the Beatles’ album The Beatles, also known as the White Album, with Jay-Z’s above mentioned The Black Album. The resulting mashup album was aptly named The Grey Album and came out in 2004. Burton’s intent was to do a limited release of his experiment but it became something bigger.

The initial limited release of The Grey Album received a lot of attention within the hip hop community and soon also attracted the attention of EMI, the record label owning Beatles’ copyrights, who pursued to cease further distribution of the album based on violations on its copyrights.

The still living Beatles members Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr had no objection for DJ Danger Mouse’s “uncleared” use of their music but it took it as a tribute and Jay-Z was also cool with it well understanding this cultural practise.

A group of music industry activists took an issue with EMI’s actions and organised a Grey Tuesday event on which the album was distributed online for free on so many websites that EMI couldn’t possibly pursue them all. The Grey Tuesday event can also be seen in a broader context of digital rights campaigning, but that’s another discussion all together.

I will leave this at here for now and come back later with another example of a more recent copyright case that also raises questions about the nature of music as an artistic and commercial practice.