I recently attended the Day on Musical instruments of the Arnold Bake Ethnomusicological society at the University of Amsterdam. This session was dedicated to musical instruments with talks and performances by musicians and scholars and closed up with a panel discussions about musical instruments in Dutch museums. The afternoon’s presentations and discussions got me thinking about musical instruments as sort of embodiment of musical cultures helping as study them as material cultures.

Representations of music

Due to the nature of music as an intangible art form, it’s most often studied using various forms of visual representations. They translate music from audible to visual form and allow disrupting the temporal flow of music. In the European art music tradition musical representation is mostly thought of in terms of musical notation. The main purpose of it is to communicate musical ideas from composer to performer and on to the listener. Interpreting the representation the performer translates it back to the temporal realm of sounding music.

This applies to much popular music as well, although most of it is not made or played from written music in a way art or orchestral music is. Vernacular music-making – or producing – nowadays is more likely to happen on computer screens where sound wave representations are manipulated to produce a form of digitalized music to be pressed on a CD, distributed as mp3 files or streamed online.

|

Sound table

|

The benefit of digital representation of music is that it can, in principle, be used for any kind of music. The only prerequisite is that it must be recorded digitally, which is not always easy e.g. when the performance is taking place outside and/or the players widely distributed in space and/or moving. As such it can be used to capture musics of oral traditions as well. Meanwhile, computers can now be considered musical instruments as well, but I’ll leave further discussion of that to another time. Jacob Collier, I’ve discussed before, is a master of “millennial” music production.

For the actual study of music, however, digital representation is of little use. It can be used to study rhythms and certain aspects of timbre and dynamics in a great detail. Any pitch related study, however, requires various sorts of analytical software to be applied.

Musical objects

Whereas representations of music are helpful for the study of music as an auditory art form, musical instruments embody a musical culture in a broader way. Musical instruments can be studied as archaeological artefacts broadening our knowledge of e.g. an ancient civilization, the music of which we don’t have representations – and the history of the human kind in general. They can also teach us a lot about the social and cultural lives of people distant in time and space. The spread of certain instruments and instrument building techniques may reveal changes in spheres of cultural influences.

Musical instruments as objects of study allow multi- and cross-disciplinary studies of musical cultures. For a while now music has offered new insights to e.g. neurologists, psychologists and architects in their respective disciplines. In the same way musical instruments can be studied by archaeologists, art historians, sociologists and anthropologists to help them form fuller understandings their fields of study – possibly with the help of some musicologists.

Material culture

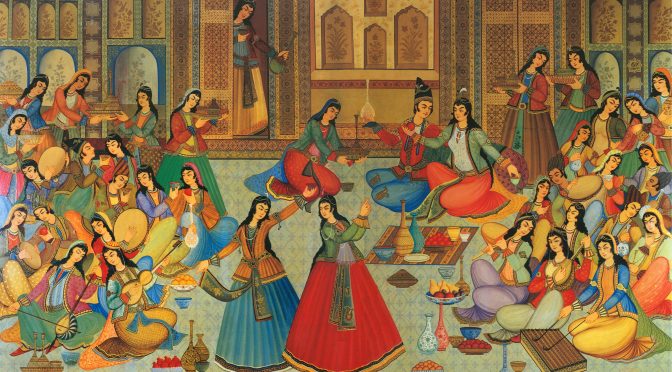

The presentations of the afternoon demonstrated the lively manner in which cultures, distant in time and space, can be studied through musical instruments. The instruments presented were not only centuries or even millennia old from different parts of the world, near and far. They were also all brought to live by the presenting musicians. One could say that we experienced what Edward W. Soja calls the Third Space; these instruments embody past, present and future geographical and social spaces and the performances, to some extent, brought those to the present and implied something of their potential future.

Ney

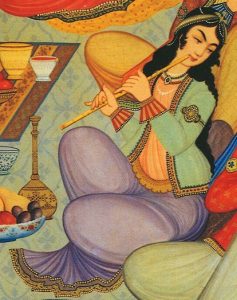

The first presentation we heard was by Sinan Arat. He first gave us a short introduction to ney and then played an improvisation with a few maqamat and some traditional melodies in between in the traditional manner of Arab music. Arat plays the Turkish ney and told us about the Ottoman tradition of the instrument.

Different kinds of flutes are some of the oldest instruments around the world but due to the simple way in which the early flutes where constructed, few very early flutes have survived. The ney has its origins in the Middle East and its history is documented in various artefacts of the ancient civilisations in the region. In Turkey the ney preceded Islam and continued to be a central instrument in the Mevlevi Sufi rituals.

Despite the relative simplicity of the instrument, the ney requires a lot of practice to even produce a decent sound on it. It’s traditionally used in religious rituals and has an important place in the mythologies of the region it hails from. According to Arat the ney is not played by blowing through it but saying “Hu” – the name of God in Sufism – into it. Although Islam doesn’t recognize music as we understand it in the West, Arat told us that he was accepted into a Turkish mosque with his ney. A frame drum is the only other instrument allowed in mosques.

In many cultures where instruments are parts of religious rituals they are learned in an apprenticeship with a master or guru; often orally as the music is not written down – or even cannot be as it’s mostly improvised. This is also the case with ney and Arat studied it with Kudsi Ergüner at the Codarts in Rotterdam. In the traditional master-apprentice manner, the studies included learning the cultural context by studying the rituals and mythologies as well as how to make and maintain the instrument.

Although the ney is an ancient instrument and deeply embedded into its cultural roots, it’s also used in contemporary music. In fact, I had heard Arat before performing with the Mehmet Polat trio. The performance was part of the Dutch Delta Sounds series in Amstelkerk in Amsterdam and showed how such old instruments – the group consists of an oud and an African Kora – can still be relevant to contemporary artists and audiences while carrying their respective cultural backgrounds with them.

The Brazilian bamboo flute pifano

Next we heard the story of, and a performance on, the Brazilian bamboo flute pifano by Ivan Vendemiatti. This flute has its origins with the farmers in the North of Brazil where it was first used to scare off birds. The rhythmic way of playing gradually developed into a music genre of its own and was performed together with drums. While fife and drums have been played in Europe and its colonies for centuries, the European tradition is strongly connected to military music. Like so many musical instruments and practices, the fife and drum tradition exists also in West Africa and the North Brazilian tradition is a typical hybrid or synchronised tradition. It’s performed in social occasions for dancing as well as in some religious processions.

What intrigued me especially in Vendemiatti’s story was that he had no musical background or education when he picked up this instrument. He had bought one on his travels and “fooled around” with it by himself before he got more seriously interested in it. He then went back to the North of Brazil and learned more about the instrument and its cultural background. Back in his native South he initiated a pifano and drum group before getting interested in the Indian bansuri flute which he now studies at the Codarts in Rotterdam.

I´ll stop here for now. Please, click below for the second part for more about the last presentation of the day as well as the very inspiring panel discussion.